Water is a fundamental human right entrenched in section 27 of the Constitution and there isn't enough of it.

Image: Nicola Mawson | IOL

Just hours before President Cyril Ramaphosa is set to deliver his State of the Nation Address, an independent democratic watchdog has called on the water crisis to be declared a national disaster.

The South African Human Rights Commission (SAHRC) said the situation has reached “crisis proportions”, with communities and households across the country battling a lack of access to water.

If declared a national disaster in terms of the Disaster Management Act, this move would unlock emergency funding and trigger a coordinated national response.

South Africans will now be desperate to hear whether Ramaphosa announces a specific “energy-style” intervention for water? South Africans want to hear about ring-fenced water budgets so that the cash paid for water goes to fixing the pipes, not paying municipal salaries.

Across South Africa’s major metros, the pattern is familiar: scheduled maintenance colliding with emergency breakdowns, all against a backdrop of ageing bulk infrastructure and high demand.

Cape Town has undergone a series of planned maintenance outages this year, resulting in area-specific cut-offs and low pressure as pipeline and connection work was carried out.

In Durban, eThekwini municipality has recorded both emergency and planned interruptions linked to works on the Southern Aqueduct and pump stations. In early February, Springtown residents endured around nine days without tap water.

Nelson Mandela Bay has experienced repeated disruptions since January, driven by power outages at water treatment works, a backlog of thousands of unrepaired leaks and falling dam levels.

Ekurhuleni has issued service alerts for emergency supply interruptions and short-term planned outages tied to maintenance on bulk infrastructure and pump stations.

In Gauteng, the strain on the bulk system has intensified. Rand Water has raised concerns about persistently high consumption in Johannesburg and Tshwane.

The utility has indicated it will reduce supply to high-consuming municipalities, which are already suffering from seamlessly endless burst pipes, to stabilise the system and has urged water-saving measures.

Johannesburg’s woes have been compounded by labour unrest with a strike involving the South African Municipal Workers’ Union having started on 6 February and is deemed unprotected.

The Democratic Alliance in Johannesburg stepped into the fray, saying services had come to a halt as workers and management sought to resolve grievances, noting that some parts of the city have been without water for well over two weeks.

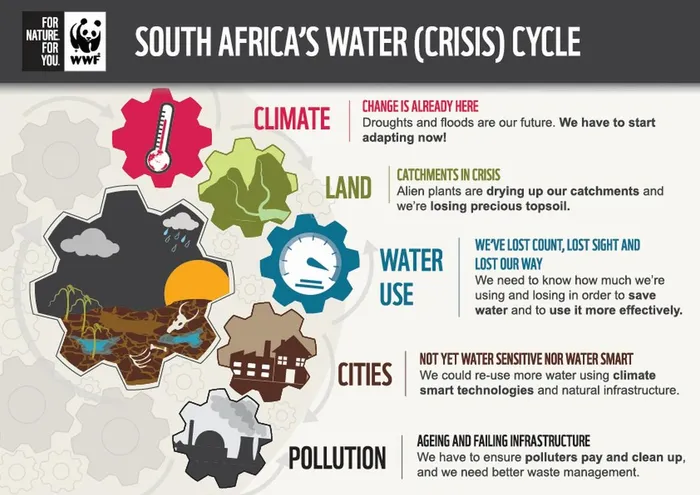

South Africa's water crisis cycle.

Image: WWF

The timing sharpens the political stakes. As Ramaphosa prepares to outline government’s priorities for the year ahead, the SAHRC has reframed water from a service-delivery headache into a full-blown national emergency.

Water is a fundamental human right entrenched in section 27 of the Constitution. The commission stressed that water is the lifeblood of human existence and underpins a range of other rights, including healthcare, children’s rights and education.

The absence of water at schools negatively affects educational outcomes, the SAHRC has previously noted, as learners are forced to miss school.

Hospitals and clinics are also hit when supply is disrupted, impinging on the right to healthcare. The commission further pointed out that the lack of access to water disproportionately affects women and girl-children, undermining the attainment of gender equality.

Behind the dry taps lies what the commission describes as an ongoing downward spiral in water management and distribution. The challenges are widespread and significantly disrupt the lives of communities, while essential services such as schooling and healthcare have been compromised.

Data from the South African Water Justice Tracker – a partnership between the SAHRC and the University of the Witwatersrand – shows that this is not a localised breakdown.

The tracker points to ageing infrastructure, an inadequate funding model, a skills deficit and poor intergovernmental coordination as key systemic drivers of dysfunction leading to a lack of water.

The SAHRC has also highlighted insufficient attention and budget allocation for infrastructure maintenance, poor planning for population growth, high levels of water losses beyond acceptable norms, shortages of skilled personnel, vandalism and the emergence of water mafias.

It has, however, cautioned that any declaration must not become a breeding ground for corruption, malfeasance or embezzlement, calling for sufficient oversight to ensure fiscal prudence.

IOL BUSINESS

Related Topics: