What if 10 cents could change the lives of farmers and end child labour? Fernando Morales de la Cruz explores how WEF participants can make a significant impact at the World Economic Forum.

Image: Supplied

Each January, the World Economic Forum meets in Davos under its motto: “Committed to Improving the State of the World”. The discussions are serious, the attendance influential, and the logistics immaculate. Coffee, tea, and hot chocolate are everywhere. I have been here 16 times.

Those drinks matter more than they seem because they are irrefutable evidence of what is wrong with the WEF.

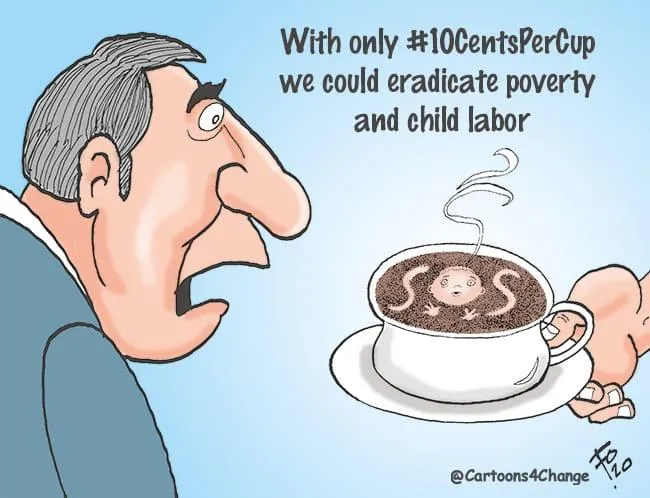

The WEF could start with a simple measure: invite all corporate members, all UN organisations, all universities and all governments present in Davos to share ten cents on every cup of coffee, tea, and cocoa they consume, serve or sell, and transfer the funds to the producers.

The proposal is modest. Ten cents would be barely noticed by WEF delegates, corporations, or institutions. But at the other end of the value chain, it would be transformative. Today, not even one cent per cup helps eliminate hunger, child labour or protect the people in the rural communities that produce these commodities.

Those rural regions face misery, hunger, infant malnutrition, child labour, and often forced labour. This is not accidental. It reflects a neo-colonial business model in which a few multinational corporations control pricing, purchasing power, and market access, while risks are pushed down to producers.

Illustration by Fo, from Guatemala, for Cartoons For Change #ZeroChildLabor.

Image: Supplied / Cartoons for Change

Certification schemes were intended to help. In practice, they have failed.

The business models behind Fairtrade and Rainforest Alliance sustain poverty, while allowing corporations to market products as “ethical” at minimal cost. Farmers remain poor. Child labour persists. Consumers are misled into thinking their purchases solve these problems. Price premiums don't deliver living incomes or wages.

This gap deceives consumers and relies on marketing that, in many jurisdictions, could be considered illegal false advertising under basic consumer-protection law. The system protects brands and certification revenues, not children or famers.

Many anti-poverty and human rights NGOs present in Davos also operate under conflicts of interest, supporting the same corporations whose practices perpetuate exploitation, in exchange for funding. This dynamic entrenches the status quo.

Coffee, tea, and cocoa are among the most traded commodities in the world. Yet most farmers and workers who produce them are paid prices below basic living costs. When farmgate prices are too low, wages are also low. When adult wages are exploitative, children work. Extreme poverty brings coercion and forced labour.

This is not a cultural failure. It is an economic one.

A small, predictable increase in price transmission — shared collectively by all WEF corporate members, UN organisations, universities and governments, and applied to every coffee, tea, and cocoa cup they consume, sell or serve anywhere in the world would multiply farmers’ income, raise wages for workers, and help bring prosperity to producing regions. Better incomes bring nutrition, school attendance, healthcare, protect the environment and help end child labour.

Ten cents would not distort markets. It would correct a long-standing imbalance.

At the consumer end, the adjustment is negligible. At the producer end, it changes incentives and outcomes. Applied globally, it would fund living wages, independent monitoring, child protection programmes, and enforcement — not labels, glossy reports, or misleading claims.

The arithmetic is uncomfortable precisely because it is clear.

For years, child and forced labour have been described on Davos panels as “complex” and “systemic”. True. But complexity has served as a rationale for delay, while certification has functioned as a commercial alibi.

Yet the economics are simple. Poverty wages create exploitation. Decent incomes reduce it.In spite of thousands of academics attending the WEF since 1971, including Nobel laureates, there has not been a serious discussion about the urgent need to implement transparent, shared-value business models across all industries that protect people and planet.

What ten cents per cup would show is that the problem is not a lack of data or expertise. It is a lack of willingness by market actors to rebalance who captures value.

Davos prides itself on turning ideas into action. If that is to be more than branding, the forum could start by asking its corporate members, UN organisations, universities and governments to act collectively. More urgently, discussions should focus on new business models that genuinely support the Sustainable Development Goals rather than oppose them, ensuring trade and governance contribute to prosperity, decency, and child protection worldwide.

Improving the state of the world does not begin with another panel.

It begins by paying people enough so their children do not have to work.

Ten cents per cup is not charity. It is justice.

What if 10 cents could change the lives of farmers and end child labour? Fernando Morales de la Cruz explores how WEF participants can make a significant impact at the World Economic Forum.

Image: Supplied

* Fernando Morales-de la Cruz is a journalist, a human rights advocate and founder of the Lewis Hine Initiatives and Cartoons For Change, working on child labour, forced labour and corporate accountability in global supply chains.

** The views expressed do not necessarily reflect the views of IOL or Independent Media.

Related Topics: